Don’t run towards an emergency. Deliberately walk.

Managing personal performance when the emergency alarm goes off.

When the continuous emergency alarm goes off in the ED - triggered by the red pull cords found in all the patient cubicles and toilet - all hell tends to break loose.

Every single clinician in the department, sometimes upwards of 20 people, will immediately abandon what they’re doing and prepare to sprint towards the source of the alarm. Just prior to setting off, there is usually at least 5-10 seconds of panic as the team try to work out exactly which alarm has been triggered, and therefore which direction to run in.

Quite often the alarm has been triggered by accident. Everyone relaxes, shares a nervous laugh, and walks back to whatever they were doing before.

But when it’s a real emergency - often a seizure, sudden drop in GCS, or full cardiac arrest - my experience, almost always, is that the arriving team don’t deliver their finest performance.

To put it less kindly… it’s (usually) a clusterf**k.

Why does the ED emergency alarm produce poor performances?

I think it’s because the team arrives flustered.

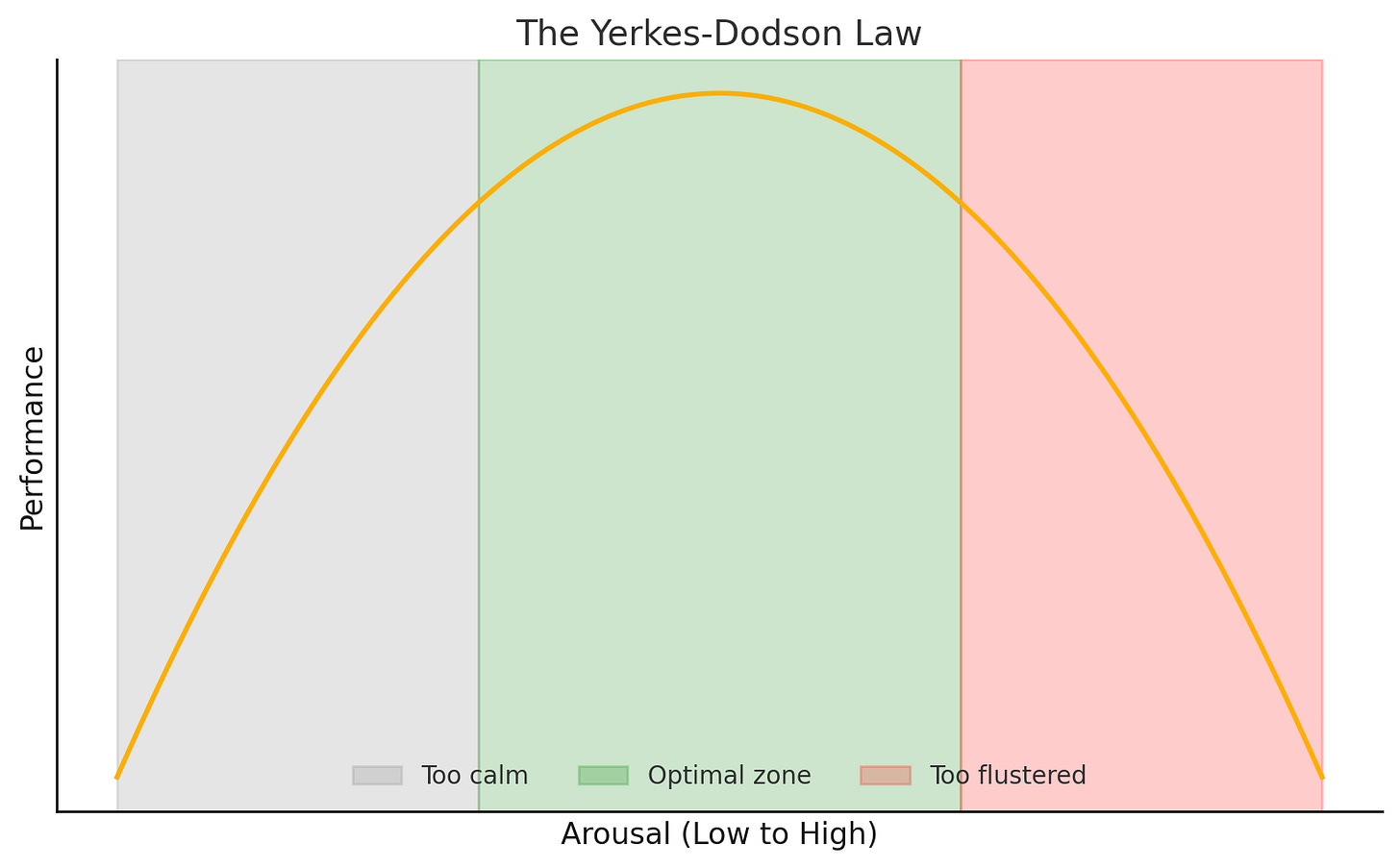

They’re in a state of emotional and physical over-arousal. The sudden, high-pitched alarm triggers a rush of emotion - excitement, nervousness, fear. The resultant catecholamine surge is compounded by the physical act of running, which further drives up heart rate, blood pressure, and respiratory rate.

This hyper-adrenalised state decimates performance.

Way too many people attend. Everyone is out of breath. Multiple team members will be properly panicking and get shouty very quickly. And if the alarm has been triggered in a very enclosed area (like a small toilet) the chaos is magnified.

Red pull cord vs “Red Phone”

When the “Red Phone” rings to alert the department a sick patient is being blue’d in by ambulance, it’s a different ballgame.

The patient is served to the receiving team in the relatively controlled, spacious and resource-flush environment that is the resus room. There are almost always a few minutes for the team to steady themselves emotionally, anticipate what will happen when the patient arrives, and build some rapport.

No-one runs to resus to receive a blue call. They walk with purpose.

Deliberate walking

I try to bring similar clear-headed, purposeful energy to emergency alarms. Whilst they don’t afford the same luxury of prep time you get with a blue call, there are still precious moments between the alarm going off and arriving at the collapsed patient where personal performance can be optimised.

Don’t run. Deliberately walk.

I use that deliberate walk as a trigger in my own mind for some positive self-talk:

“Time to lead. Keep it simple”.

I try to encourage others not to run where possible, though this is often futile as most people have already hurtled off at maximum speed. En route I’ll also start thinking about resus capacity – if I know it’s dire I’ll try and get the nurse-in-charge to work on expediting a stepdown to make space.

These days it’s usually appropriate for me to assume a leadership role (I am a now consultant of course 😬). My deliberate walk usually means I arrive just after the rest of the team. I’ve found that arriving slightly later actually makes it easier to step into the role of team leader, because my first move is always the same: crowd control.

I’ll usually only want/need an ED nurse, a resident doctor, and an obs machine in the cubicle initially. That’s unless it’s a cardiac arrest, in which case we’ll need more hands for CPR and to facilitate a rapid move to resus.

I like to slowly and calmly raise my voice:

“Not everyone needs to be here”.

I try to follow this up with clear instructions (using first names if I can) about who stays and who goes.

I’m not out of breath so won’t sound flustered, and I’ve arrived last so won’t need to repeat myself for stragglers. Less noise, more action.

Cheers all,

Robbie

@robbielloyd.bsky.social

References:

Yerkes, R. M., & Dodson, J. D. (1908). The relation of strength of stimulus to rapidity of habit‐formation. Journal of Comparative Neurology and Psychology, 18(5), 459-482.